Early Surveys of First Nation Reserves in Alberta

By Gordon Olsson

The first surveys of reserves for First Nations in what was to become the province of Alberta were carried out in 1878 by Dominion Land Surveyors William Ogilvie and Alan P. Patrick. It was a time when First Nations were faced with the reality of living on reserves under the treaties. This article will tell about the relationship between the Crown and First Nations peoples, often in the words of the surveyors and bureaucrats themselves and it will tell about the challenges and tensions as the work of surveying the reserves proceeded.

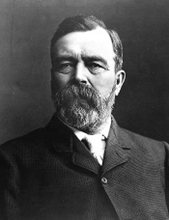

William Ogilvie. He qualified as a Dominion Land Surveyor (DLS) in 1872. He surveyed in the North-West for the department of the Interior from 1875 to 1887. During the Yukon Gold Rush he was engaged in sorting out and arbitrating indiscriminate staking of gold mining discovery claims in the Yukon where he gained a reputation for integrity and reliability. In 1898 Ogilvie became Yukon’s second Commissioner. A mountain range, a river, and a valley in the Yukon are named after him.[i]

Alan Poyntz Patrick. He qualified as a DLS and a DTS (Dominion Topographical Surveyor [ii]) in 1877. Prior to becoming a DLS and DTS he had considerable survey experience working in Ontario, Manitoba and the North-West Territory. In 1881 Patrick settled in Calgary where he opened a survey practice. Beside many other endeavours, he was involved in oil exploration, was Justice of the Peace for the Northwest Territories for many years and in 1915 he became an alderman for Calgary. [iii]

The relationship between First Nations and surveyors began well before the surveying of reserves following the signing of the treaties. From the early 1700’s, explorers and surveyors such as Alexander Mackenzie, David Thompson and Anthony Henday, amongst others, relied on First Nation’s knowledge of the terrain and its inhabitants to explore and map new territories for the fur trade. The relationship was mutually beneficial. European demand for pelts, particularly that of the beaver, was lucrative for the traders, while in return, First Nation peoples gained access to European goods.

However, as time passed, the power dynamics shifted. By the 19th century, European diseases such as smallpox and measles had decimated the First Nations population, who lacked natural immunity. Furthermore, by the late 1870’s, the buffalo, a staple of their diet, had dramatically declined due to overhunting. The introduction of alcohol, which was exacerbated by American whiskey traders in the 19th century, also contributed to First Nations poverty.[iv] With the decline of the fur trade, the Hudson’s Bay Company – which had controlled trade and the administration of Rupert’s Land since 1670 – sold the land to Canada in 1869. In 1870, Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory were incorporated into the Dominion. This was followed by the Dominion Lands Policy of the 1870’s, which promoted settlement and agricultural development on the prairies. Under the Royal Proclamation, the Dominion government was obligated to negotiate treaties with First Nations before settling the land. The transfer of Rupert’s Land to Canada also required Canada to address Aboriginal claims. In a desolate, weakened, and impoverished condition, and recognizing the inevitable intrusion of settlement, most First Nation leaders realized that their only viable choice was to agree to treaties and accept the wardship of the Crown.

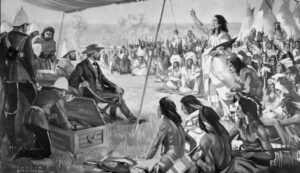

On the right, speaking with his arm raised, is Chief Crowfoot with an interpreter beside him. Treaty 7, 1877, Seated is Colonel Macleod and Lieutenant Governor Laird, in civilian dress. Painting by A. Bruce Stapleton. Digital Collections, University of Calgary. Na-40-1.tif.

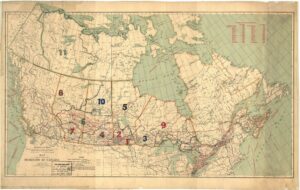

The Numbered First Nation Treaties. Map of the Dominion of Canada,

Department of the Interior, 1929. CLSR F4078.

Eleven treaties, negotiated between 1871 and 1921, known as the numbered treaties, were in the area that is now covered by the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario, and the Northwest Territories. Five of these treaties (4, 6, 7, 8 and 10) pertain to present-day Alberta; however, only three (6, 7, and 8) contain First Nation reserves.

Treaty No. 6 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Plain and Wood Cree was signed at Fort Carlton, Fort Pitt, and Battle River in 1876. It was followed by several adhesions.

Treaty No. 7 between Her Majesty the Queen and the Blackfoot (Siksika), Blood (Kainai), Piegan (Piikani), Sarcee (Tsuut’ina) and Stoney-Nakoda was signed on September 22, 1877. The treaty provided one large reserve for the Blackfoot, Blood, and Sarcee along the Bow and South Saskatchewan Rivers, with separate reserves provided for the Peigan and Stoney-Nakoda.

Signatories to Treaty 7 (Blackfoot Confederacy): Left to right: Three Bulls (Siksiká), Eagle Tail (Piikani), Crowfoot (Siksika), Red Crow (Kainai).

Treaty 8, between Her Majesty the Queen and the Cree, Beaver, and Chipewyan, which covered most of the northern part of the province, was not signed until 1899. It was not negotiated at the time of Treaties 6 and 7 because the area it covered was less accessible and sparsely settled. However, by the late 1890’s, increasing settlement and development began to interfere with First Nations land rights, making a treaty for the area desirable.

Following the signing of the treaties, it was the responsibility of Dominion Land Surveyors working for the federal Department of the Interior to survey the reserves. The Department was created in 1873 with a broad mandate that included managing public lands, natural resources, and overseeing settlement and development in the North-West. The Department was also responsible for Indian Affairs. During 1880, the Indian Branch of the Department of the Interior became a separate department and assumed control of reserve surveys in Manitoba and the North-West Territories.[v] They then hired their own surveyors, who became known as “Indian Department Surveyors”.[vi]

In some cases, as in Treaty 7, the location of the reserves was specified in the treaty. In other cases, an agent of the Crown, often the surveyor who was to survey the reserve, determined a suitable location in consultation with the First Nation. In a meeting with the Cree on August 19, 1876, Lieutenant-Governor Alexander Morris stated: “as you may not have all made up your minds where you would like to live. … We would send next year a surveyor to agree with you as to the place you would like.” [vii] The surveyor also had to ensure that the area complied with the land allocated by the First Nation population. The provisions in Treaties 6, 7, and 8 allocated one square mile for each family of five persons, or in that proportion for larger and smaller families.

Alan P. Patrick and William Ogilvie, who worked for the Department of the Interior, were sent out from Ottawa to survey reserves for the Indian Affairs Branch of the Department of the Interior in the spring of 1878. Although Treaty 6 was signed in 1876, the year before Treaty 7 was signed, Treaty 7 reserves most likely were surveyed first because they were located near the proposed route of the railway and were in the fertile belt, making that area the most likely to be settled first. In addition to surveying the reserves, Ogilvie and Patrick were instructed to locate and map topographical features of the region they were working in, as very little information was known of the area at that time.

Patrick left Ottawa on May 15, 1878,[viii] with Ogilvie following a few days later on May 20. Ogilvie travelled by train to Sarnia, where he boarded the lake steamer Quebec, arriving in Duluth on Saturday, May 25th. He stayed there for one day before leaving for Glyndon (near present day Fargo, ND) on the 27th. In Glyndon, he left on the Red River Steamer for Winnipeg, arriving on May 30th. On June 4th, after hiring his field party and purchasing his outfit, he left Winnipeg for Battleford, the capital of the North-West Territories. Travelling overland by horse and cart with his assistant, three men, and a cook, he arrived in Battleford on July 6th.[ix] The exact date that Patrick arrived in Battleford is not known, but it likely preceded Ogilvie’s by a few days.

In Battleford on July 9th, Ogilvie received a telegram from Colonel John Stoughton Dennis, the Surveyor General, naming him and Patrick to conduct the surveys for Treaty 7. In Battleford, Ogilive also conferred with Lieutenant Governor David Laird, who was also superintendent of Indian Affairs, about the surveys. Ogilive noted in his report that the Lieutenant Governor “thought it would be very imprudent in view of the numerous rumors which were the rife of disaffection among the Indians in the Southwest and of the presence of a delegation from the American Sioux Indians whose mission was not yet understood – to send any party to said treaty and desired me to remain quiet until the arrival of Colonel McLeod.” On July 16th, Colonel McLeod, Commissioner of the North-West Mounted Police, arrived and reported that everything was favorable for the start of the surveys. [x] On July 23rd, Lindsay Russell, Assistant Surveyor General, gave the surveyors final instructions for the surveys. However, neither Ogilvie nor Patrick could leave as their supplies had not arrived. Finally, with supplies in hand, on August 5th, they left to start the survey for the large reserve for the Blackfoot, Blood and Sarcee.

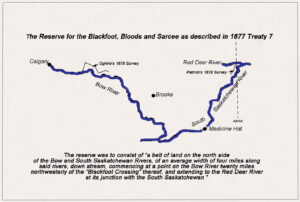

The reserve, as described in Treaty 7, was to consist of “a belt of land on the north side of the Bow and South Saskatchewan Rivers, of an average width of four miles along said rivers, downstream, commencing at a point on the Bow River twenty miles northwesterly of the “Blackfoot Crossing” thereof, and extending to the Red Deer River at its junction with the South Saskatchewan.” [xi]

Patrick was to start his survey at the eastern end of the reserve at the junction of the Red Deer and South Saskatchewan Rivers. The junction is notable as it borders Treaty 4, 6 and 7 lands. Ogilvie’s survey which was to start at the western end at Blackfoot Crossing is described later.

Patrick reached the junction on August 15th. Late in September, after about a month’s work, the Cree Chief, Big Bear (Mistahi-maskwa) arrived at Patrick’s camp with about 100 followers. Even though the land was in Treaty 7 territory, Big Bear, who had refused to sign Treaty 6, said: “that the country we were in belonged to the Cree and that they wished no kind of work proceeded with by the surveyors or any other white men”.

Chief Big Bear (Mistahi-maskwa). He was a Cree chief who had resisted signing Treaty 6 believing that the conditions were unfair and would destroy his people’s way of life. His defiance drew a large following of independent warriors to his camp and by the winter of 1878-79 he was at the height of his influence. He eventually signed Treaty 6 on December 8, 1882, when faced with having rations for him and his followers cut off. Library and Archives Canada. MILKAN 3629644.

Following the confrontation with Big Bear, Patrick proceeded to Fort Walsh to report the incident to the North-West Mounted Police and subsequently returned with the Assistant Commissioner. After the intervention of the Police, Patrick reported that: “Big Bear offered no further resistance.” Patrick, however, having heard from Colonel MacLeod that the reserve boundaries were likely to change and with severe storms approaching, finished the work he had in hand and proceeded to Fort MacLeod. His assistant, John C. Nelson, went to Fort Walsh with the Assistant Commissioner, conducting an odometer survey of the road and mapping topographical features along the way.[xii],[xiii]

It was not until late in the summer of 1879 that Patrick was able to survey the Peigan and the Stoney-Nakoda Reserves, which were the other two reserves in Treaty 7.

Edgar Dewdney, Indian Commissioner for the North-West Territories, in mid-July was involved in determining the location of the Peigan Reserve. In his annual report for 1879, Dewdney wrote: “On my return to Fort MacLeod, I met by appointment “White Swan” (one of the Piegan chiefs) on the ground that they had intimated, at the time of the treaty, they would like for their reservation, and which was promised them. I had also directed Mr. Patrick, P.L.S.[xiv], to be there, in order that the boundaries might be agreed upon, and the survey made at once. An understanding was arrived at, and I proceeded to Fort MacLeod, “White Swan” having expressed his determination to settle down, and follow both agriculture and stock raising.”[xv]

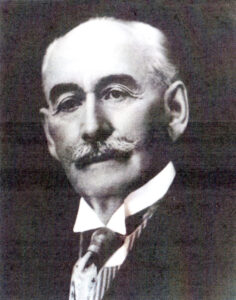

Edgar Dewdney. He emigrated to British Columbia from England at the age of 24 in order to act as surveyor for the Dewdney Trail that ran through the province. He served as Indian Commissioner in the North-West Territories from 1879 until 1888 and also as Lieutenant Governor from 1881 to 1888. In 1888 he became Minister of the Interior.[xvi]

The survey of the Peigan Reserve was started on July 13, 1879.[xvii] Immediately after, Patrick left his assistant Nelson to complete the survey, and he accompanied Dewdney to Calgary to determine a reserve for the Stony-Nakoda. In a report to Lindsay Russell from Fort Walsh on January 12, 1880, Patrick wrote” Immediately after the survey of the Peigan Reserve was begun in accordance with Mr. Dewdney’s desire, I accompanied him to Calgary in order that a reserve might be decided upon for the Stony Indians. I instructed Mr. Nelson to complete the Peigan Reserve, the survey of which I found upon my return most satisfactory made.”[xviii]

On August 6th, after the survey of the Peigan reserve was completed, the entire survey party left Fort MacLeod for Calgary and then proceeded to Morleyville to lay out the reserve for the Stoney-Nakoda[xix]. At the end of the season, Patrick wintered in Fort Walsh.

In 1880, as soon as the weather moderated, Patrick surveyed a reserve of about 340 square miles in the vicinity of Elkwater along the northern slope of the Cypress Hills for the Assiniboine, a signatory of Treaty 4. However, shortly after the survey was carried out, the Indian Department decided to relocate the Assiniboine from Cypress Hills. Although the Assiniboine people fought the relocation from their ancestral lands they eventually were forced to move when faced with starvation as an alternative.[xx] They eventually were moved to Carry the Kettle Reserve near Indian Head, Saskatchewan. As a result, there are no reserves established under Treaty 4 in Alberta. In 1880, after surveying several more reserves in Saskatchewan for the First Nations under Treaty 4, Patrick returned to Ottawa in December. [xxi]

In a report written in Fort Walsh dated January 12, 1880, to the Surveyor General regarding his 1878 and 1879 seasons, Patrick made this observation of the First Nations peoples of the North-West:

“I am perfectly aware that it is somewhat out of my province to make any remarks on the Indians of the North-West; but, nevertheless, after an intercourse of some two years with the original occupants of the soil, I cannot refrain from mentioning what I think a matter of the utmost congratulation, namely: that all our relations with them have been, with the exception of the slight misunderstanding with Big Bear, friendly. Had this been otherwise, our work might on several occasions been seriously interfered with, if not stopped, for a considerable length of time. The Indians while the buffalo were in the country, were in the position of well-to-do traders; the robes furnished them with means to barter, and thus enabled them to supply themselves with clothing, blankets, ammunition, etc., the meat of the buffalo supplied food in ample abundance. Now, however, such a state of affairs does not exist, the Indian, in the absence of buffalo, is in truth a pauper; though, thanks to the judicious policy of the North-West Mounted Police, he is tractable and, generally speaking, law-abiding.

The various tribes of Indians on the plains have invariably, when without food, secured help at police posts. The Indian thinks this help comes from the Great Mother, the Queen; his powers of discrimination are not great, and to his mind any man or men in the employ of the Government are bound to help him in time of need. When buffalo were not to be found, I at various times was forced to supply large quantities of food to Indians knowing them to be in a starving condition.” [xxii]

William Ogilvie, the other surveyor assigned to survey the large reserve for the Blackfoot, Blood, and Sarcee reached Blackfoot Crossing at the western end of the reserve on September 6th after locating topographical features enroute.[xxiii] With regard to the location of the survey, he wrote in his field book report: “His Honor instructed me verbally to make the Westerly boundary of the Reserve on Bow River start from a point on the river 20 miles in a straight line from Blackfoot Crossing on it which I did as shown in the notes and on the plan.”[xxiv] His Honor referred to was Lieutenant-Governor David Laird.

At Blackfoot Crossing, Ogilvie was met by an unwelcoming gathering of approximately seven hundred Blackfoot who had gathered there to receive their treaty money. When they would not let him proceed with the survey Ogilvie sought out Chief Crowfoot.

Chief Crowfoot. He had a reputation as a great orator, peacemaker, and diplomat. He realized that the traditional free nomadic life of buffalo hunting was coming to an end and the tide of settlement in the North-West could not be stopped.[xxv]

In 1912, Ogilive recounted his incident with the Blackfoot and Chief Crowfoot: [xxvi]

“I reached Blackfoot Crossing on Bow River, the last place I was to locate, and where the real work of my orders from Ottawa began, in the afternoon of the tenth of September.[xxvii] Here I found the Blackfeet with their Chief, Crowfoot, gathered to the number of seven hundred, awaiting the arrival of the agent with their treaty money. Some miscreant had told them that surveyors were coming to lay out their reserve, build a high wall around it, drive them into the enclosure and keep them there for all time to come. I saw at once that something was wrong, but what, I could not make out. Though they did not lay hand on me they would not let me, or any of the party do anything, not even build a fire, and the more we tried the worst humor they seemed to be in. Not knowing what was the matter, and dreading a rupture, I was delighted to hear one of the band around me say something in French, in which at the time I could make myself fairly well understood. I enquired for Chief Crowfoot, letting it be known as well as I could, that I wanted to satisfy him as to what was to be done with regard to the survey. Fortunately there was a French-Canadian in the camp who had acted as a Missionary with the Band for years, and spoke English, French and Blackfoot. He was very cordial, and with his aid I soon came to an understanding with the Chief, who was a very sensible old gentleman. He gave instructions to his people that I was to be allowed to carry on my work without interruption.”

Following this encounter, Ogilvie completed his survey without further interference, finishing on October 22nd, which concluded his field season. He left for Fort McLeod on October 25th, arriving on October 28th. On November 10th, he arrived at Fort Walsh, and he arrived in Winnipeg on December 30th. After paying his men and selling his outfit, he left Winnipeg on January 6th, arriving in Toronto on January 9, 1879.[xxviii]

Sketch showing the location of Ogilvie and Patrick’s 1878 surveys of the reserve for the Blackfoot, Blood and Sarcee.

The Treaty 7 provision to have one large reserve on the north side of the Bow and South Saskatchewan Rivers for the Blackfoot, Blood, and Sarcee began to collapse in the summer of 1878. During that summer, Cecil Denny, an inspector of the North-West Mounted Police, informed Crowfoot that Red Crow, Chief of the Blood, had decided his tribe should have their reserve further south along the Belly River and that Colonel MacLeod was in agreement.[xxix] Crowfoot was the de facto leader amongst the Blackfoot when Treaty 7 was negotiated and at the time had obtained the agreement of both the Bloods and Sarcee for one large reserve for all, along the Bow and South Saskatchewan Rivers. Crowfoot believed that united tribes on one large reserve would give them greater bargaining power and a position of strength in their dealings with the white man. As well, the area encompassed some of the best game country in the area.[xxx]

This was bitter news for Crowfoot. It was MacLeod who in 1874 led the North-West Mounted Police column to Southern Alberta. He had largely achieved his mission, which was to establish law and order, eliminate the whiskey trade in the area, and establish a strong dialogue with the First Nations. Both Crowfoot and Red Crow respected and trusted him; and he was one of the commissioners appointed to negotiate Treaty 7.[xxxi]

One would think with the news from Cecil Denny that the surveys of the Blackfoot Reserve would be halted, but it was likely that the reason no action was taken was because nothing official had been decided. By 1881, it was accepted that the Blackfoot, Sarcee, and the Bloods would have separate reserves. That same year, John C. Nelson, who had recently qualified as a DLS, was employed by Edward Dewdney to survey reserves for the Department of Indian Affairs.[xxxii] Soon after, he became in charge of all reserve surveys in the North-West.

On June 28th , 1881, on the way to the field, Nelson had a friendly conversation with Chief Crowfoot: “I told him that I had returned again to this country to make further surveys of Indian Reserves; and that I would possibly survey the reserve for his band in the fall, after completing the survey of the reserves for the other tribes of Blackfeet”.[xxxiii]

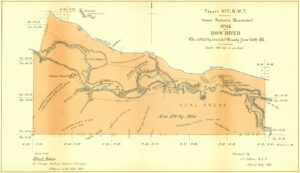

After completing the surveys for the Sarcee, Blood and Peigan, Nelson proceeded in October 1881 to survey the Bow River with a view of defining the Blackfoot Reserve. The understanding was that the Blackfoot would be entitled to a tract of land one hundred and twenty miles in length by four miles deep on the north side of the Bow and South Saskatchewan Rivers, as their share of the large reserve originally intended for the Blackfoot, Bloods, and Sarcee. However, in his 1881 report to the department, he said: “When the time comes for settling this matter the Blackfeet most likely will see the advantage to themselves of having their reserve laid out as shown by the accompanying sketch, instead of having it as described by the Treaty; the object they had then in view of excluding half-breed and other hunters from occupying the river bottoms, being now no longer necessary, by reason of the disappearance, from that country, of the buffalo.” [xxxiv]

In 1983, Nelsen surveyed a large tract of land south of the Canadian Pacific Railway line on both sides of the Bow River for the Blackfoot. The sketch mentioned in Nelson’s 1881 report was not located during the writing of this article, so to what extent it was followed could not be determined; however, the plan to survey one long, narrow reserve was abandoned.

New treaties were signed in 1883: with the Blackfoot on June 20; with the Sarcee on June 27 and with the Bloods on July 2. In the treaties reserves were allocated as surveyed by Nelson, with the Blackfoot as described, with the Sarcee for three townships west of Calgary and with the Bloods for land between the Belly and St. Mary Rivers. In these treaties the three First Nations also released their rights to the large reserve allocated in the 1977 treaty. [xxxv]

Edgar Dewdney, in his 1883 report to the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, reported that “all the Indians in Treaty 7” were content with the boundaries agreed upon. [xxxvi] From all reports, Nelson had an excellent relationship with the First Nations. Dewdney reported that Nelson, while surveying the reserves, took great pains to take the chiefs with him and that he pointed out to them the reserve boundaries. [xxxvii] In another report an Indian Agent states: “Nelson’s patience, fairness and desire to give satisfaction was appreciated by the Indians”. [xxxviii] Nelson himself in 1882 reported: “Chief Bull’s Head and the Sarcee are perfectly delighted with their reserve as now surveyed. This band have always considered the Elbow as their country, and their hearts were set on the place they call Ki-aiks-eh, which lies between Fish Creek and the Elbow River, and now in the reserve.” [xxxix] Nelson also hired First Nations peoples and, as a rule, he only gave employment “to Indians living on the reserve on which the work was being performed.” [xl]

In 1887, Nelson prepared a compilation of survey plans and descriptions for approximately 80 Reserves in what was then the province of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. This compilation was used for the confirmation of Reserves by P.C. 1151 on May 17, 1889. The compilation is commonly referred to as Nelson’s Book.” [xli]

Nelson’s 1883 Survey of Blackfoot Reserve. CLSR FB6062 (Nelson’s Book)

What happened to the 1878 surveys by Ogilvie and Patrick? Ogilvie’s field notes and plan are in the Canada Lands Survey Records (CLSR). When the new Blackfoot Reserve was surveyed in 1883, it was located in the same area as that surveyed by Ogilive, and some parts of Ogilvie’s survey were still relevant. However, there is no record of Patrick’s survey at the junction of the Red Deer and South Saskatchewan Rivers in the CLSR.

Author: Gordon Olsson, ALS (Hon. Life)

May 20, 2025

Copyright 2025 © Alberta Geomatics Historical Society

End Notes

[i] Surveyors of the Past, The Canadian Surveyor, June 1978. Don W. Thomson, Men and Meridians, Vol 2, Chapter 9.

[ii] Additional examinations were required to become a DTS. The survey of the controlling lines for the Dominion Land Survey were carried out by DTS’s as extensive knowledge of geodesy and astronomy was required.

[iii] Glen R. Belbeck, Calgary’s Grand Old Man A.P. Patrick, Alberta Land Surveyor, 2022.

[iv] Sid Marty, Firewater: The Impact of the Whiskey Trade on the Blackfoot Nation. albertaviews, January 1, 2018.

[v] J.S. Dennis DTS, Chief Inspector of Surveys, Dominion Lands System 1869 to 1889. 55 Victoria, Sessional Papers (No 13.) A. 1892. Page 22.

[vi] Stanley A. Hutchinson, A History of Indian Reserve Surveys in Alberta, April 1982, Prepared for the Alberta Land Surveyors’ Association as a requirement for Alberta Land Surveyor certification. The department of Indian Affairs was responsible for reserve surveys until 1936 when the Surveyor General again was made responsible for them.

[vii] Morris, Alexander The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. Toronto, 1880; reprinted Coles Canadiana, 1971. Page 205.

[viii] A.P. Patrick, Report to the Surveyor General Lindsay Russell, Fort Walsh, 12th January, 1880.

[ix] Diary of Wm Ogilive, 1878. CLSR Field Book 804.

[x] Report of Wm. Ogilive in his field book for the 1877 Survey of Blackfoot Reserve. CLSR Field Book 803.

[xi] Indian Treaties and Surrenders, Volume 2, 1891. Pages 56 to 62.

[xii] A.P. Patrick, Report to the Surveyor General Lindsay Russell, Fort Walsh, 12th January, 1880.

[xiii] Glen R. Belbeck, Calgary’s Grand Old Man A.P. Patrick, Alberta Land Surveyor, 2022. Pages 97 to 106. Belbeck in his book provides two other sources of the story, each with a slightly different version.

[xiv] Patrick was also a Provincial Land surveyor (P.L.S.) P.L.S. stands for Provincial Land Surveyor, a designation used for a qualified surveyors in Ontario at the time.

[xv] 1879 Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs. Report from Edgar Dewdney, Indian Commissioner for the North-West Territories to the Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs, January 2, 1980.

[xvi] Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Edgar Dewdney.

[xvii] Canada Lands Survey Records: FB1896ACLSRAB. A note on page 1 reads: “July 13th- 1879 – Survey of Peigan Reserve – Commenced” Generally Patrick’s field notes are poor and contain few dates. The last date shown in the field book is August 5 when an observation for azimuth was taken. As well there no diaries for Patrick in the CLSR.

[xviii] A.P. Patrick D.T.S Report to the Surveyor General Lindsay Russell, Fort Walsh, 12th January, 1880.

[xix] A.P. Patrick Report to the Surveyor General Lindsay Russell, Fort Walsh, 12th January, 1880.

[xx] Carry the Kettle First Nation Inquiry, Cypress Hills Claim, Indian Claims Commission, July 2000.

[xxi] Glen R. Belbeck Names from the Past: Allan Poyntz Patrick, PLS, CE, DLS/DTS, LS(BC), JP, ALS, The Baseline The Newsletter of the Alberta Geomatics Historical Society. March 2025.

[xxii] A.P. Patrick Report to the Surveyor General Lindsay Russell, Fort Walsh, 12th January, 1880.

[xxiii] Diary CLSR 804, Field book CLSR 803.

[xxiv] Field book CLSR 803, Page 99.

[xxv] Hugh A. Dempsey Crowfoot – Chief of the Blackfoot, 1972.

[xxvi] Wm Ogilvie, Reminiscences of Camp Life on Surveys in the North-West During the last Thirty Years, Program of the Association of Dominion Land Surveyors at its Sixth Annual Meeting held at the Carnegie Library, Ottawa. March 5th and 6th, 1912). The incident is also recorded in Ogilvie’s field book CLSR 803 and in his diary, field book CLSR 804.

[xxvii] Note: The date September 10 is likely wrong. In his diary CLSR 804 Ogilvie’s writes that he reached the crossing and met Crowfoot on September 6. Also his field notes of the survey CLSR 803, also show him arriving on the 6th.

[xxviii] Diary of Wm Ogilive, 1878. CLSR 804. Field Notes, , CLSR 803.

[xxix] Hugh A. Dempsey, Crowfoot – Chief of the Blackfoot, 1972, pages 104, 109-110.

[xxx] Hugh A. Dempsey, Crowfoot – Chief of the Blackfoot, 1972, pages 104, 109-110.

[xxxi] Hugh A. Dempsey, Red Crow – Warrier Chief, 1980, pages 104,105104, 109-110.

[xxxii] Library and Archives Canada. – John C. Nelson’s personnel file as Dominion Lands Surveyor for the North-West Territories, Images 86, 87, 88.

– Edgar Dewdney recommending that John C. Nelson be employed as a surveyor of Indian Reserves in the North-West Territories.

[xxxiii] 1882 Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs.

[xxxiv] 1882 Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs.

[xxxv] Indian Treaties and Surrenders, Volume 2, 1891. Pages 128 to 138.

[xxxvi] 1883 Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs.

[xxxvii] 1883 Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs.

[xxxviii] 1887 Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs, Report by John A. Mitchell, Indian Agent, Peace Hills Agency.

[xxxix] 1882 Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs.

[xl] 1889 Annual Report of the Department of Indian Affairs.

[xli] CLSR Field Book 6062. Nelson’s Book.