THE SURVEY OF THE ALBERTA-BRITISH COLUMBIA BOUNDARY 1913-1924

By Gordon Olsson

For territorial limits of First Nations or geographical limits of sparsely settled land, a boundary defined by a natural feature, even though it’s exact location may be unknown, was satisfactory. Such was the case of the part of the boundary between Alberta and British Columbia that followed the continental divide of the Rocky Mountains. For centuries it had formed a natural boundary for First Nations and fur traders.

While negotiating Treaty No. 8, the government of Canada made the following observation: “As the Indians to the west of the Mountains are quite distinct from those whose habitat is on the eastern side thereof, no difficulty ever arose in consequence of the different methods of dealing with the Indians on either side of the Mountains, But there can be no doubt that had the division line between the Indians been artificial instead of natural, such difference in treatment would have been fraught with grave danger and have been the fruitful source of much trouble to both the Dominion and the Provincial Governments.” The Rocky Mountains also became the boundary of the territory granted by Charles II of England in 1670 to Prince Rupert and his “Company of Adventurers of England, trading into Hudson Bay”. The charter set the geographical limits of this territory as the source of the streams that drained into the Hudson Bay. Therefore, one of the boundaries of this land was the line of the watershed of the Rocky Mountains.

It was only natural as the west developed that the Rocky Mountains would become a boundary for administrative and political areas. When Alberta and British Columbia were set aside as provinces, it followed that the Rocky Mountains would form part of the common boundary. In the early 1900’s, with the discovery of valuable deposits of coal and timber and the construction of roads and railways in the mountains, the need to know the exact location of the boundary became more important. As a result, in 1913, the governments of British Columbia, Alberta and Canada established the Alberta-British Columbia Boundary Commission to survey and map the boundary. Three Boundary Commissioners were appointed: Arthur O. Wheeler, DLS, OLS, MLS, ALS, BCLS representing the government of British Columbia; Richard W. Cautley, DLS, BCLS, ALS representing the government of Alberta; and John N. Wallace, DLS, OLS, ALS representing the government of Canada.

By mutual consent of the three governments, it was arranged that the work of the boundary Commissioners be carried out under the instruction of Dr. Edouard Deville. Dr. Deville, who was Surveyor General of Dominion Lands from 1885 to 1924, introduced the method of photo-topographical surveying that was applied by the Boundary Commission surveyors in mapping the watershed. Dr. Deville’s instructions described the boundary to be mapped and surveyed as the line dividing the waters flowing into the Pacific Ocean from those flowing elsewhere. The boundary was to start at the US/Canada International Boundary, then follow the watershed line (of the Rocky Mountains) to the 120th degree of longitude and then follow the meridian of longitude to the 60th degree of latitude, which was the northern boundary of Alberta and British Columbia. The instructions continued with more details on how the boundary should be surveyed. Where the watershed line was sharp and well defined, it would only need to be mapped. In the passes, where the land was flat or rolling, or where there could be some doubt as to the position of the boundary, a series of straight lines defined by monuments was to be established in the general direction of the watershed. The instructions also included a list of the parts of the boundary requiring first attention, a description of the type of monuments to be placed, and the responsibilities of each Commissioner.

Édouard-Gaston Daniel Deville

Besides Deville’s contribution to photo-topographic mapping, nearly the whole of the land survey of Western Canada was carried out under his direction.

Library and Archives Canada, Mikan 3214864

The mapping of the watershed, where it was well defined, was the responsibility of the British Columbia Commissioner, Arthur O. Wheeler. The work was tailor made for Wheeler. He had over thirty years’ experience as a land surveyor and was one of a handful of surveyors proficient in the photo-topographical method of surveying introduced by Deville. He was also experienced in mapping mountainous areas and was an accomplished mountaineer. In fact, his interests in mountaineering extended beyond that required for his work to such an extent that he is perhaps better known as a mountaineer than a surveyor. He was instrumental in forming the Alpine Club of Canada, was the club’s first president, and served as a director for 20 years.

Photo-topographical surveying required a specially constructed camera and mountain theodolite. The camera and theodolite were carried to control stations which were located on mountain peaks or on other high places. From these control stations, photographic plates were exposed to be developed later in the office. The mountain theodolite was used to read the direction of the angles between control stations and to read the directions to which the photographs were taken. The observations were required to bring order to the photographs so that the maps could be made later in the office.

A.O. Wheeler at Assiniboine Pass 1916

Library and Archives Canada 4876285

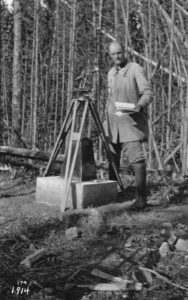

The Alberta boundary commissioner, Richard W. Cautley, was responsible for surveying the boundary in the passes. Cautley was an experienced surveyor, having obtained his first commission in 1896. Although Cautley was responsible for the surveys in the passes, the location of the monument positions was decided collectively by the Commission. This work was not always straightforward. Often the passes were very flat, were in muskeg or marsh, or had lakes or landlocked areas where drainage was not evident, making the boundary difficult to determine. In all of these cases, special rules were established by the Commission to provide guidance in defining the location of the watershed. Cautley’s survey work in the passes consisted of building monuments on the boundary, cutting out and measuring the lines between the monuments, observing astronomical azimuths, and measuring angles between the lines.

R.G. Cautley at Monument 95F 1914

Library and Archives Canada 4876261

Both Wheeler and Cautley started work on the boundary in Kicking Horse Pass during the summer of 1913. The altitudes above sea level of all of the monuments and points of the survey for the photo-topographical work were derived by trigonometric levels from control points previously established by the Topographical Division of the Department of the Interior. The triangulation survey used to establish positions of the control stations were connected to the boundary survey at each pass. An important part of Cautley’s work was to connect the boundary survey with the nearest lines of the Dominion Lands Survey System or with other surveys so that checks could be made for the overall accuracy of the work.

The third boundary Commissioner, J.N. Wallace represented the interests of the Canadian government, and it was his job to monitor the surveys, particularly in the passes. Prior to the start of the survey, he worked closely with Wheeler and Cautley in formulating the survey requirements for the boundary. In the first few years of the survey, as the boundary in each of the passes was completed, Wallace would travel to the site to inspect the boundary with the other Commissioners. For these trips, it was not uncommon to leave his home in Calgary early in the morning, travel to the nearest point of access to the pass being surveyed and then walk 20 miles or more to the camp of either Wheeler or Cautley before inspecting the boundary the next day. Wallace’s involvement only lasted a few years as it was later decided that Cautley could represent the interests of both the Alberta and Canadian governments.

Although he had a reputation as a taskmaster, Wheeler had the respect and loyalty of those who worked for him. As Wheeler was very involved with the Alpine Club of Canada, he often left his assistant, Alan J. Campbell, in charge of the party for long periods of time. Conrad Kain, a renowned Austrian guide also worked on the survey. Under Kain’s tutoring, Campbell overcame an initial fear of mountain heights and became a proficient mountaineer. Also assisting Wheeler was Alan S. Thomson, Although Thomson also worked in the field, his main responsibility was in the office compiling the maps from the hundreds of glass plates which had been taken during the surveys.

Monument 11A in Kicking Horse Pass. The man on the right

appears to be Conrad Kain, Austrian mountain guide.

Alberta Director of Surveys Office

The diaries and reports of the Survey contained numerous accounts of adventure, hardship and danger. Occasionally, there were encounters with grizzly bears. Days were long: six hours of climbing to the camera station, three or four hours observing, and about three hours descending was a normal day’s work. Pack horses often lost their footings in rivers or on steep mountain slopes, resulting in injury or loss of equipment. In August 1913, while fording the Vermillion River on the way to Simpson Pass, one of Cautley’s horses lost its footing and was carried downstream. The horse was rescued but the pack containing the survey instruments was lost. As a result, Cautley had to travel all the way back to Edmonton to obtain replacements. On another occasion, the head packer on Cautley’s party drowned while attempting to rescue a pack horse that had fallen off the trail and had swum to the other side of the Kananaskis River. It was a sad loss. The packer, Jacob Koller, had been a member of Cautley’s party from the time the work had started, a period of nearly four years.

A.J. Campbell and A.S. Thomson

in a crevasse on Mt. Chaba Glacier

Alberta Archives A10725

Camera stations were often on precarious peaks or ridges. Often ice fields and glaciers had to be crossed. During the 1918 field season, work was carried out north of Howse Pass, which is between Lake Louise and Jasper, The terrain was so rugged that it prohibited the use of horses and all equipment and supplies had to be carried on the backs of the field party. On one occasion, while crossing the Conway Icefield, the leader of the party broke through a snow crust and fell into a hidden crevasse. Fortunately, the party had been roped together and he was able to be rescued. To add to the problems, the men hired for the survey usually had no or little experience in mountain climbing. In 1918 this contributed to a serious loss while descending Coronation Mountain. Campbell had just finished lowering two inexperienced members of the party down a steep cliff when he lowered the knapsack containing the field notes with the measurements from the previous several days’ work. One of the members untied the knapsack and placed it on a ledge. Unfortunately, the ledge was too narrow, and the knapsack bounded out of sight to glacier ice below. Two days searching in pouring rain, in every accessible spot, was to no avail. As a result, the party had to return to repeat the measurements, a process that took 10 days.

In addition to surveying the boundary through the passes, Cautley surveyed the boundary along the 120th meridian. When the Commission was first established, the 120th meridian was of little importance to the governments involved. However, as settlers moved into the Peace River area, subdivision surveys became necessary and the need to define this part of the boundary became urgent. In 1918, Cautley began surveying the 120th meridian. From 1918 to 1924, even though he continued surveying the passes on the watershed, most of his time was spent working on the 120th meridian.

Cautley’s Crew on the Summit of Mt. Torrens while

Surveying the 120th Meridian in 1922.

Library and Archives Canada 5039446

The watershed portion of the Alberta-British Columbia boundary took 12 years to survey and map and was completed in 1924. Over 1100 kilometres of watershed boundary was mapped and surveyed. A special monument was erected in Robson Pass to commemorate the completion of the survey. The commemoration was held in conjunction with the annual summer camp of the Alpine Club of Canada. On July 31, 1924, members of the English, American, Appalachian, French, and Swiss Alpine Clubs joined the Surveyor General of British Columbia, the Deputy Minister of Lands for the province, J. N. Wallace, and C.N.R. and C.P.R. executives on the summit of Robson Pass between Berg and Adolphus Lake. Also present was F.H. Lambert from the Dominion Geodetic Survey who worked on the boundary survey from 1922 to 1924 establishing a triangulation survey that the boundary surveyors could connect to. As a tribute to the invaluable work of Wheeler’s assistant, A.J. Campbell, Mrs. Campbell was given the honour of unveiling the memorial monument. R.G. Cautley was working elsewhere on the boundary and was not able to attend the commemoration.

Cairn and 5 men “The final and historic monument of the Alberta-BC Boundary” Mt. Robson Pass.( L to R) F.H. Lambart, G.R. Ngden (BC Deputy Minister of Lands), J.E. Umbah (BC Surveyor General), A.O., Wheeler, J. N. Wallace (Dominion Director of Levels and Boundary Commissioner 1913-1915).

Library and Archives Canada PA-202781

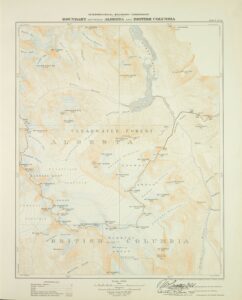

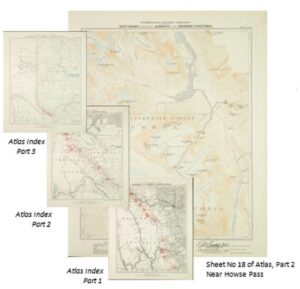

The returns of the survey included reports of the commission appointed to delimit the boundary. Three books were published by the government of Canada: Part I (1913 to 1916) from Kicking Horse Pass to the International Boundary, Part II (1917 to 1921) from Kicking Horse Pass to the Yellowhead Pass, and Part III (1918 to 1924) from the North of the Yellowhead Pass to the Northwest Territories. The books include a history of the various passes surveyed, descriptions of the topography, notes on flora and fauna, and a chronology of the survey with many anecdotes. Each part is accompanied by an atlas: Part I – 27 maps; Part II – 23 maps; and Part III – 30 maps. The topographical maps in the atlases were magnificent detailed works of art.

Sheet No 18 of Atlas, Part 2

The survey not only provided a demarcation of the boundary, but it also provided topographical and scientific information about one of the world’s most magnificent and remote areas. In addition, the work of the Commissioners did much to stimulate interest in the mountains and in the Canadian National Parks. Since the completion of the boundary survey, only a handful of surveys have been required usually to further define the boundary where new development was taking place or to restore monuments. This more than anything else is a tribute to the skill, dedication and professionalism of the original Boundary Commissioners.

References and Further Reading:

- Jay Sherwood’s two books: Surveying the Great Divide 1913-1917 and Surveying the 120th Meridian and the Great Divide 1918-1924, Catlin Press, 2017 and 2019. A must read for anyone interested in learning more about the survey of the boundary.

- Order in Council Setting Up Commission for Treaty 8, P.C. No. 2740

- Peter C. Newman, Company of Adventurers, Penguin Books Canada Ltd, I985, pages 94-87, 324, 121.

- Esther Fraser, Wheeler, Sunmerthought Ltd., Banff, Alberta, 1978, pages 52, 96, 104.

- Report of the Commission Appointed to Delimit the boundary between the Provinces of Alberta and British Columbia, Ottawa, Part 1, page 121.

- Report of the Commission Appointed to Delimit the boundary between the Provinces of Alberta and British Columbia, Ottawa, Part 11, page 29. 31.

- Olsson G.E. The Survey of the Alberta-British Columbia Boundary, Boundaries, ALS News Spring/1988.

Author: Gordon Olsson, ALS (Hon. Life)

March 15, 2024

Copyright 2024 © Alberta Geomatics Historical Society